🇮🇹 Versione italiana

Vatican City - In recent days, many noticed that Vatican News quietly removed several images by the artist and former Jesuit Marko Ivan Rupnik. The move—carried out without a single word of explanation—has sparked questions and controversy, intensifying growing frustration with the current leadership of the Dicastery for Communication, headed by Paolo Ruffini, Andrea Tornielli, and Andrea Monda. The timing of this removal—923 days after Silere non possum’s exclusive report on December 1, 2022—is particularly awkward.

Let us not forget: Rupnik incurred a latae sententiae excommunication, disobeyed all imposed restrictions, and was eventually expelled from the Jesuit order. To make matters worse, the canonical trial that should have followed never happened, reportedly blocked by the ongoing protection he received from Pope Francis. While rumors—strategically leaked to journalists—claimed that the Pope had lifted the statute of limitations and thus opened the door to prosecution, the truth tells a different story. That process was stalled internally by Francis himself, who ensured it wouldn’t take place during his pontificate.

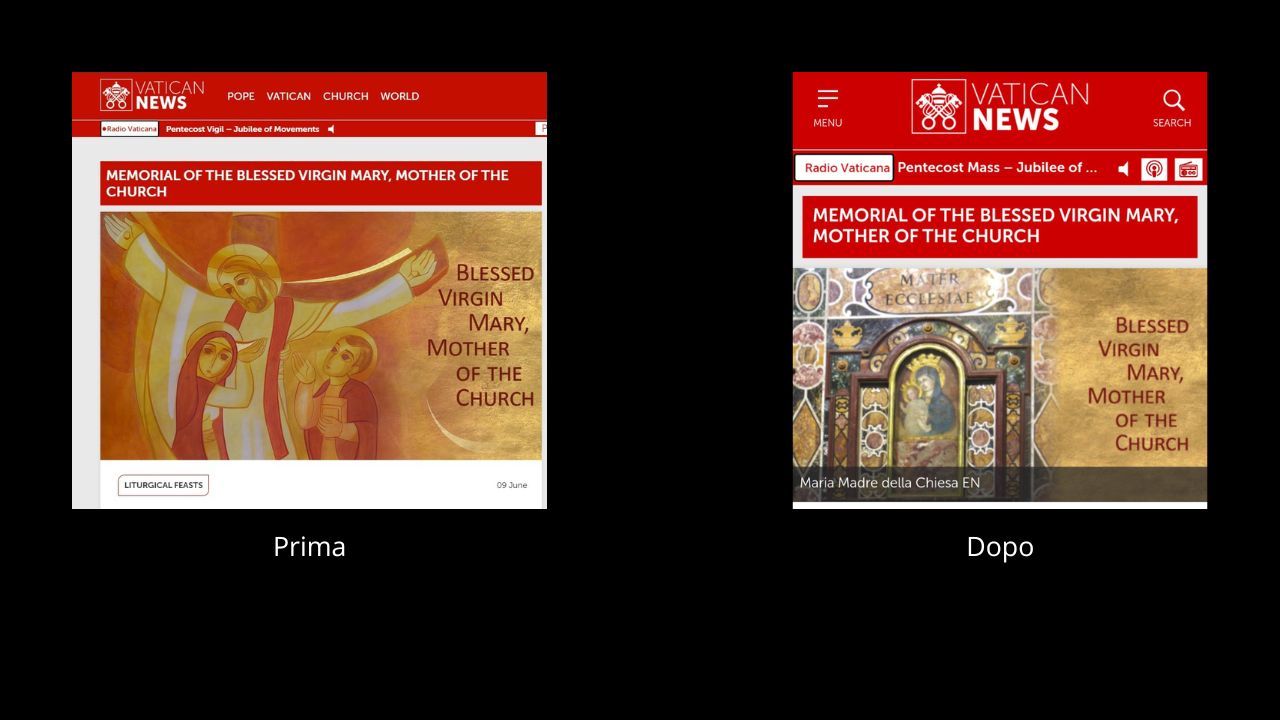

Yet despite all this, Rupnik’s images continued to appear on the Holy See’s official communication platform, illustrating Gospel reflections and liturgical events.

So the obvious question is: why now? Why remove the images so quietly, after years of debate and criticism surrounding Rupnik? What we can say for certain is that, at long last, someone within the Vatican walls finally had the courage to speak up and make their discontent known—even reaching as far as Piazza Pia.

The Embarrassing Paradox of the Dicastery for Communication

In clerical circles, many are asking: how can the Dicastery for Communication—a body created specifically to ensure clarity, transparency, and proper handling of information relating to the Holy See—remain completely silent on the Rupnik affair? Isn’t it a paradox, even a contradiction, that the Vatican’s official communication arm would act in secret, quietly deleting images without explanation, while other institutions within the Church have openly distanced themselves from Rupnik?

A dicastery that should be a beacon of transparency instead appears unable to rise to the occasion, resorting to covert actions and offering no public rationale. And the implications go far beyond the simple act of removing artwork.

Rupnik and Those He Protected—Who Now Protect Him

The Rupnik case doesn’t begin or end with a trial that never took place or with the deletion of a few images. It is part of a much broader network that involves key figures within the Vatican, such as Monsignor Dario Edoardo Viganò—infamous for the controversy over the doctored letters of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI. Rupnik himself was a supporter of Viganò, and his influence appears to have played a significant role in shaping positions within the Dicastery—positions more reflective of internal political maneuvering than of genuine pastoral need.

Thus, the Rupnik case isn’t just about him. It calls into question the credibility of an entire system, one that includes bishops whose careers were shaped by this Slovenian priest. The appointment of Nataša Govekar—a known collaborator of Rupnik—to a key role within the Dicastery for Communication only deepens this contradiction. Her nomination raises serious questions about the competence and integrity of internal decision-making. It appears that some positions exist more to guarantee paychecks for those linked to certain circles than to ensure effective communication.

Laity and Transparency

Transparency within Church institutions has become a topic that easily draws clicks and headlines—even in secular and international media. In places like Switzerland, the Church has been accused of failing to offer adequate clarity on abuse cases, feeding a narrative of "cover-up" that often lacks foundation in the actual documents. Nevertheless, the perception persists—and it’s one of the most common charges leveled against Church leadership: that they care more about preserving reputation than addressing problems openly and truthfully.

But when we examine the behavior of the Dicastery for Communication, it’s hard not to see a serious inconsistency. On the one hand, Andrea Tornielli speaks out against clericalism and its toxic power structures. On the other, decisions are being made by laymen, in silence and behind closed doors, with no explanation to the faithful. This dicastery—tasked with being the Church’s voice in complex and sensitive times—often ends up looking like a fortress defending entrenched power, rather than an institution genuinely dedicated to honest, open communication.

The comparison with what happens just down the road in Italian political institutions isn’t far off. There, as here, we see a dense network of laypeople shielding each other to maintain influence and job security. In this light, Pope Francis’s decision to rename the former “Congregations” seems almost prophetic. Our institutions, it seems, have become so secularized that we’ve placed the future of the Church in the hands of laity more interested in power than in service—laity who are loyal not to the Church, but to the people who put them there.

Which Way Are We Headed?

The quiet deletion of Marko Ivan Rupnik’s images from Vatican News is yet another sign of a lay-run communications office that refuses to be transparent and fails to take public responsibility. It's yet another misstep from Andrea Tornielli and his team, who in recent years have accumulated more blunders than accomplishments. If these people, tasked with overseeing and directing the work of others, can’t even fulfill their own basic duties—why are they being paid? To write twenty-line editorials lifted from more successful Catholic outlets?

When the Dicastery for Communication—supposed to be the Church’s lighthouse for transparency and clarity—falls into the trap of silence, we have to ask: what future is there for Vatican communications? Do we really want to continue down this path—installing people in power not for their merit or competence, but because they have powerful patrons who protect them even in disgrace?

In a time when trust in the Church is already fragile, there is no room for more cover-ups or silence. If the very office that receives millions of euros each year to communicate on behalf of the Holy See can’t manage to do so with basic clarity, then who will?

d.T.A.

Silere non possum