Vatican City - «Some reports have reached this Dicastery». Mark this phrase well: from 29 May 2018 to today it has functioned like a mantra, repeated until it became a hammering refrain for many members of the Fraternity of Communion and Liberation and of the lay association Memores Domini.

That formula has, in practice, been transformed into a language of governance. It is also in this way that, over these years, the entire movement of Communion and Liberation has been pushed to modify its way of looking at reality: from a gaze upon the person - the gaze that Giussani taught, handing on that gaze upon the human being that Jesus had - to a lexicon made up of “they said that”, “perhaps it happened”, “reports have arrived, therefore there must be something”, all the way to allusions to “unspeakable things” attributed, “perhaps but one does not know”, to Tom, Dick or Harry. We are faced with a method of governance which, while having oriented choices and practices throughout an entire pontificate, remains distant from an evangelical criterion. It serves above all to manage dissentand to close off, in a summary manner, what one does not wish - or is unable - to address with law and charity.

The decisive point is technical: this formula does not record a fact. It does not circumscribe a charge. It does not clarify who reports, what is reported, under what circumstances, with what evidence, nor to whom any responsibilities are attributed. It instead produces a precise effect: it constructs a context, an environment of power, a framework in which the mere existence of “reports” becomes sufficient to trigger measures, reviews, warnings. It is from this nerve centrethat one must begin in order to establish the truth of this story. When a report remains anonymous, is not verifiable and is not subjected to a review capable of ascertaining its substance, it ceases to be an investigative element and becomes a crowbar. It activates decisions without the persons involved being able to know the origin of the accusation, assess the credibility of the objections, refute them with contrary elements and defend themselves within a recognisable canonical procedure, with guarantees, timeframes, acts and responsibilities.

In such a mechanism, the centre of gravity is no longer the fact, but the climate; and the climate, when it finds adequate backing, ends up weighing more than the evidence. Here we are not dealing with a simple opinion or a stance taken by a newspaper, a politician, a commentator: we are speaking of an official body of the Holy See that acts upon persons, upon human beings who have given their lives to Christ within a movement. Someone may imagine that “Dicastery”, “Church”, “Vatican”, “Holy See” are spaces in which to exercise power like in a game, entering and leaving at will – a dynamic typical of certain lay environments. For one who has given his entire life to the Church, for a priest even more than for a consecrated lay person, it does not work that way at all. His life depends, in every respect, on this authority. An official body must act according to law, within clear and verifiable rules. It would be unthinkable for an Italian citizen to be summoned by the police to give explanations on the basis of a complaint that, however, “we cannot show you”. The same principle must also apply to a Dicastery: justice requires it, the Code of Canon Law imposes it, and the concrete protection of the persons involved demands it.

Carrón and Pope Francis

Let us proceed in order. In February 2018, during a private audience with Pope Francis, don Julián Carrón places on the table a datum that he considers by then evident: within the movement there is a difficulty in following him, and that tension had been growing since 2015. It matures precisely in those environments which, while lamenting difficulties and malaise, had meanwhile already activated a network of contacts and friendships to reach the Pope directly, obtaining audiences and forwarding letters then channelled to the Dicastery for the Laity, the Family and Life; a passage situated in the context in which, in November 2017, Francis appoints Linda Ghisoni as Undersecretary of that same Dicastery, a figure linked by personal relationships to Andrea Perrone, known on the occasion of various meetings promoted by the Centre for Studies on Ecclesiastical Bodies and Other Non-Profit Entities of the Università Cattolica, of which Perrone is president. At the end of that audience, Carrón concentrates everything into a question that seeks guidance and measure: «if you had something to tell me, because we desire nothing other than to follow you». In the background there returns an episode from the previous year (2017): the donation of the Fraternity of CL to the Pope after the pilgrimages of the Jubilee of Mercy and Francis’s response with a letter on poverty, a thank-you that immediately becomes a call to a style, to a concrete detachment, to a conversion in the way of looking at and using things; Carrón states this without ambiguity, acknowledging that that letter «dictated the content of the most recent Fraternity Spiritual Exercises», where, in April 2017, poverty is taken up as a criterion-word because it points to what is essential: «it describes what we truly have in our hearts: the need for Him».

The beginning of a Calvary

In the private audience of February 2018, Carrón also raises with the Pope a question of governance: with his mandate set to expire in 2020, he asks Francis which path to take; Bergoglio urges him: «We have common enemies, go forward». A few weeks later, in April 2018, at the Fraternity Spiritual Exercises in Rimini on the theme: «Behold, I am doing a new thing: do you not perceive it?», Cardinal Kevin Joseph Farrell, Prefect of the Dicastery for the Laity, the Family and Life, is invited: during the meeting he raises no objections, on the contrary he offers words of confirmation, even going so far as to say - in an Italian that he himself defines as “special” - that «you are the presence of Christ in the world» and that the task entrusted is «to be the real presence of Christ in the world». On that occasion, accompanying him by car to the Exercises were Andrea Perrone and Mario Molteni. A ready-made narrative had already been delivered to the Cardinal, but during those days he did not seek a direct confrontation with don Carrón, did not request a private meeting, did not summon persons to be heard in order to verify, seek corroboration, compare versions. He did not initiate any investigation, nor did he let transpire any sense of urgency for further examination: nothing that would have hinted at the arrival of a decisive turning point. For this reason, when the Exercises concluded, in Communion and Liberation no one imagined that shortly thereafter an intervention would change the entire life of the movement, affecting the lives of many and opening a long season marked by suffering and internal rifts.

On 29 May 2018, from the Dicastery for the Laity, the Family and Life, a “PERSONAL/CONFIDENTIAL” letter is issued that follows a script already seen in many curial communications: paternalistic tone, careful construction, polished lexicon to make palatable what is about to come. It begins with a benevolent part, even recalling the “congratulations” for the private audience of February with the Pope and recognising the value of the Fraternity’s work. Then the formula is triggered which, as usual, arrives like a sharp blade: «I find myself… having to notify you» that reports would have arrived from members of Memores Domini concerning an alleged discrepancy between the 2013 Directory and the Statute. It is here that the text begins to creak: the intervention is presented as a technical reaction to internal reports, but without indicating facts, names, circumstances, without delimiting a verifiable chargeand without offering a verifiable perimeter upon which one can truly discuss. And yet, in the first point, the Dicastery immediately reaches the real target, defining as “problematic” Carrón’s personal situation – the coincidence between President of the Fraternity and Ecclesiastical Counsellor of Memores – and transforming into a suddenly decisive issue an arrangement that had been known, practised and never formally contested for years: a passage that resembles less the discovery of an irregularity and more the launch of a change of line, prepared with language that sounds neutral while shifting the axis from the norm to the person.

The Dicastery declares that it has “examined with particular care” the Directory, comparing it with the Statute and the previous Directory (1989), and constructs two levels of objection: on the one hand the structure of governance and charism (responsibility for the “educational path”, guarantee of “immanence” in the Church, the “primary and ultimate” role of the Ecclesiastical Counsellor); on the other hand the more sensitive - and moreover very noble – terrain of conscience, confidentiality, distinction between internal forum and external forum, even evoking the risk of abuses of authority and calling upon, as a moral seal, a phrase of Pope Francis on the grave abuse involved in mixing the two fora. The critical point, however, is that this preventive architecture prepares the intervention without having to demonstrate a concrete abuse: the category of abuse is introduced as a systemic possibility, while the final request (“to realign” and to present a proposal for amendment) takes the form of an invitation and the substance of a command, placing Carrónin an asymmetrical position: he must respond and adapt; therefore, he is already within the perimeter of oversight.

The critical issues of the intervention

There are several issues that must be clarified immediately, and it is an information portal that has for years conducted investigations into abuses of conscience that does so. A portal that has not allowed itself to be intimidated by pressures exerted to prevent the publication of news on the Rupnik case, and that was the first to break the silence on this complex case; a portal that, with the same continuity, denounces abusive drifts also on the part of certain bishops to the detriment of presbyters. A portal that for years has explained how necessary it is to prevent through affective and human formation, both in seminaries and in lay realities. At this point it is necessary to separate the planes, without ambiguity. One thing is a contested, proven and circumscribed abuse. Another thing is the temptation to construct a sort of psycho-police: a device that does not address abuses, but ends up striking “enemies” on the basis of the hypothetical possibility that “perhaps”, “who knows”, “it could” occur. The result, in that case, is not the protection of persons, but the production of a climate useful to justify interventions already decided at the drawing board for motivations completely different from abuses.

Also in this intervention of the Dicastery, if the objective had truly been to correct a text that could potentially open margins of abuse, there would have been no problem: oversight of norms, when conducted with transparent criteria, is part of responsible governance. Moreover, it is precisely this task that belongs to the Dicastery, and “prevention is better than cure”. The problem – and we will show it on the basis of documents, audio recordings of Prefect Farrelland the Undersecretaries with Memores Domini, audio recordings of conversations of Pope Francis and much other content – is that that intervention did not substantially aim at the modification of the Directory or the Statute. It aimed elsewhere: to reach a knot of persons and structures, eliminating those who were inconvenient to someone in his exercise of power.

The Dicastery maintains that it examined the Directory and Statute with “particular care”. Yet, more than a careful reading, what emerges is the impression of a removal of the history of the movement, of the Fraternity and of the lay association Memores Domini. The assessments taken up seem in fact to replicate, almost without filter, the arguments that Perrone, Molteni, Cesana and others presented in an instrumental manner to open a breach in the Dicastery, leveraging a theme certainly delicate and today particularly sensitive in ecclesial debate. The point is simple: if those objections had been submitted to those who truly know the history of Communion and Liberation, they would hardly have produced the effect they produced. The peculiarity of certain norms was known, discussed and evaluated at the highest levels: by Benedict XVI and Cardinal Stanisław Ryłko, then President of the Pontifical Council for the Laity. For this reason, the question that someone should have posed immediately to these “illustrious lawyers” and “eminent defenders of Catholic doctrine” is elementary: if the text was approved in 2013, why do these instances arrive only in 2018? And, if one truly wished to act in an evangelical (Matthew 18:15–18) and orderly manner, a preliminary step would have been inevitable: did you present these observations to the Governing Council? Because here there is a decisive detail that seems to have been conveniently set aside: the Directory was not approved by the Ecclesiastical Counsellor, but by the Governing Council. And it is there that, before knocking on Roman doors, the confrontation should have been opened.

In 2013 and until September 2016, in Rome it was difficult to “knock” with certain instances: guiding the then Pontifical Council for the Laity was Cardinal Stanisław Ryłko, who knew closely the history of Communion and Liberation and the figure of don Luigi Giussani. Ryłko, a man of trust of Saint John Paul II and then maintained in his role also by Benedict XVI, followed for years precisely the world of lay movements. He passed through, as a privileged observer, the time of the great impetus to movements during the pontificate of the Polish Pope and, subsequently, the season of normalisation and of “bringing back into line” initiated under Ratzinger. To him, moreover, Benedict paired his former personal secretary.

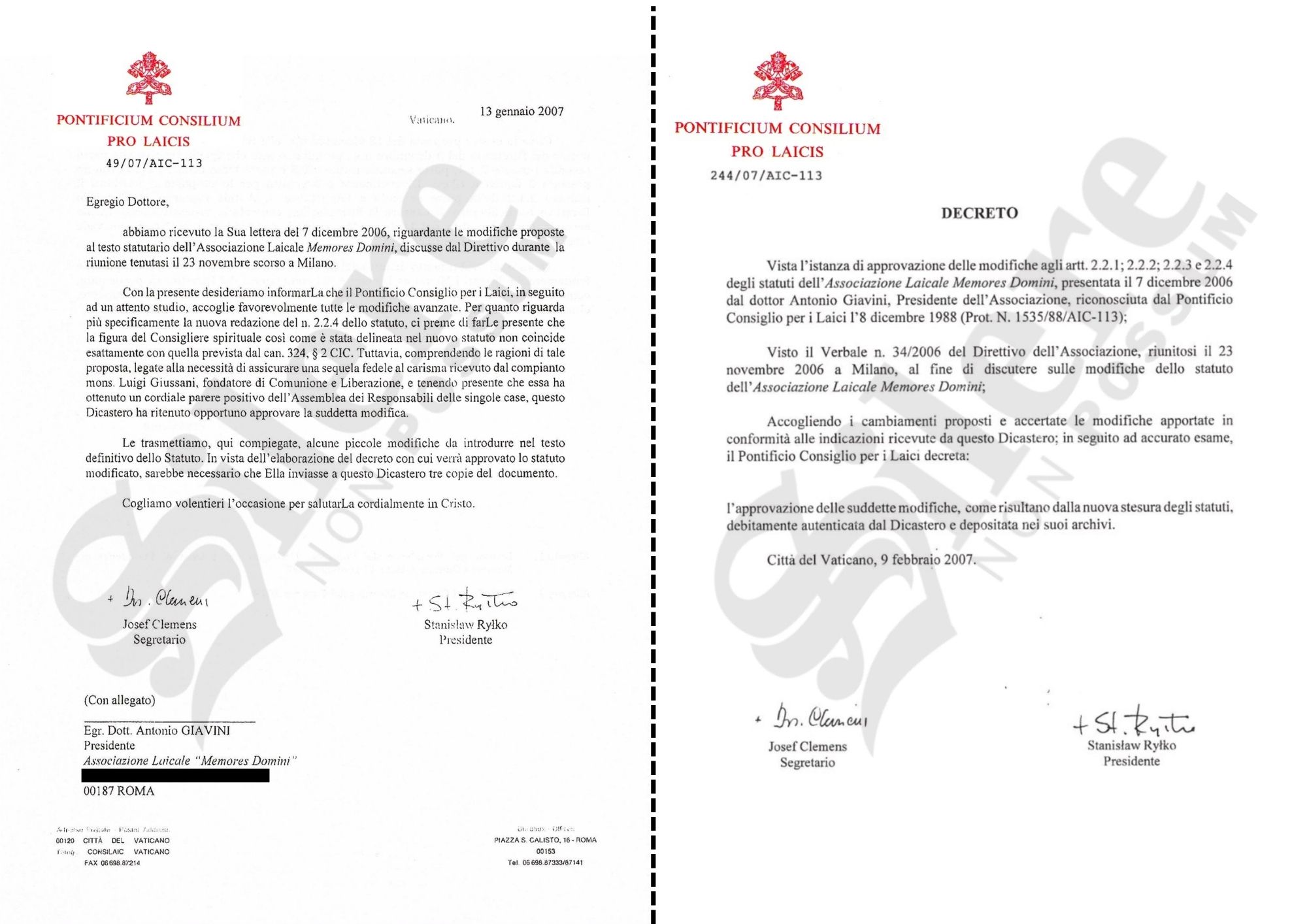

It was precisely they who signed, on 13 January 2007, the letter (copy below) by which the new Statute was approved, “discussed by the Governing Council during the meeting held on 23 November in Milan”. In that document, which formally accompanied the statutory text, the two prelates wrote: “With the present letter we wish to inform you that the Pontifical Council for the Laity, following careful study, favourably receives all the proposed modifications. As regards more specifically the new wording of no. 2.2.4 of the Statute, we wish to inform you that the figure of the Spiritual Counsellor as outlined in the new Statute does not exactly coincide with that provided for by can. 324, §2 CJC. However, understanding the reasons for this proposal, linked to the need to ensure a faithful following of the charism received from the late Msgr Luigi Giussani, founder of Communion and Liberation, and bearing in mind that it has obtained a cordial positive opinion from the Assembly of the Heads of the individual houses, this Dicastery has deemed it appropriate to approve the aforementioned modification.” At this point the dynamic is clear. If in 2013/2014 someone had brought the question to the Pontifical Council for the Laity, the response would in all likelihood have arrived in the form of an interpretative note, capable of explaining the reasons for that choice and of bringing the matter back within its proper perimeter. The affair would, in all probability, have ended there. But precisely here lies the knot: because the intentions were very different from the proclaimed “protection” against possible abuses of conscience, it is difficult to imagine that someone would have gone then to knock on that door with the same complaints.

Still further…

Ignorance of the law, unfortunately having become a constant in recent years also within the Roman Curia, has produced enormous damage: it has broken lives, destabilised entire realities, and in not a few cases has opened the way to abuses and oppression. But how can one claim to prevent abuses – even those defined as “potential” – if one does so by trampling the law? It is exactly what happens when one acts in a manner contrary to what the Code of Canon Lawprescribes. Canon 17 is very clear: «Ecclesiastical laws are to be understood according to the proper meaning of the words considered in their text and context; if they remain doubtful and obscure, recourse must be had to parallel places, if any, to the purpose and circumstances of the law and to the mind of the legislator».

This is, in fact, the approach adopted by the “new Dicastery”, with the “new Prefect” and the “new Undersecretary”. But if there is one lesson that the Church has had to learn over these thirteen years, it is precisely this: a pontificatecannot claim to wipe out history, previous pontificates, the experiences matured and the recognised charisms. And if there is something that even the College of Cardinals has understood with greater clarity during the recent Conclave, it is the urgency of continuity. Ecclesial life does not function like an ordinary change of government, in which a majority takes over and rewrites everything in opposition to those who were there before. One cannot upheave people’s lives from one day to the next as if it were a political alternation: today one decides in one way, tomorrow everything is cancelled out of a pure spirit of contradicting predecessors.

The Church cannot reason with categories of institutional cheering sections. It is not conceivable to proclaim a sainttoday and tomorrow treat him like the anti-Christ. And yet, in these years, a dynamic has often been fuelled that has ended up calling everything into question, transforming discontinuity into a criterion. This does not hold, neither theologically nor pastorally, because it undermines trust and renders arbitrary even what yesterday had been recognised as a positive, innovative peculiarity proper to a charism. If a choice is evaluated, at a given moment, as coherent with the identity of an ecclesial reality, it cannot be used the next day to claim that “everything was wrong” and to strike those who had “obeyed”, without a serious, documented argument, and above all without respect for the persons involved. All the more so when it is done by that same reality which repeats like a mantra that one must obey what the Church says because it is always right. In this way one asks for obedience to a principle and, at the same time, empties it from within. Because the issue does not end with the texts. In 2008 and 2013 the Pontifical Council for the Laity, always under Ryłko’s guidance, appointed as Ecclesiastical Counsellor precisely the President of the Fraternity of Communion and Liberation. Why? What canonical logic and what reading of the charism supported that choice, if today the same architecture is presented as a problem to be removed? If the text is read in context – as the Code requires and as Cardinal Ryłko and Archbishop Clemens recalled in the 2007 letter – the Ecclesiastical Counsellor was considered an integral part of the Governing Council. The competences attributed to him cannot be extrapolated as if they were a “separate” power: they fell within a logic of co-responsibility towards the Association and were to be interpreted within the overall architecture provided for by the Directory and Statute. The Prefect’s objection, instead, put in parentheses a decisive datum: those provisions had been conceived as a safeguard of confidentiality and of the necessary discretion in the most serious personal situations. Without that perimeter, the risk was the opening of paradoxical scenarios. The associate would, in fact, have lost the possibility of addressing the Ecclesiastical Counsellor directly. A member of the Governing Council, having become aware of delicate circumstances, would not have had an ordered channel to submit them to discernment before they flowed into a collegial circuit. And the protection of personal intimacy would have been weakened, because every case would have been forced to pass through the House Responsible and/or a collegial level, with an evident harm to freedom and protection of the person.

There was then a further interpretation that was incomprehensible: the Dicastery ended up confusing the theme of the governance of the association with the internal forum. Associative discipline – read in the light of the norms on private associations of the faithful – did not authorise commingling between external forum and internal forum, nor did it legitimise the improper identification of the internal forum with “conscience” as an undifferentiated category. The Counsellor was called to serious discernment, not to perform the function of a disciplinary intermediary. Finally, an essential aspect was neglected: spiritual accompaniment could be carried out by other priests freely chosen. The function entrusted to the Ecclesiastical Counsellor – and, with analogous limits, even the figure of the visitor provided for by the Directory – proved to be delimited and non-substitutive: it did not create a new decision-making centre, did not override the responsibles, did not establish autonomous “educational” or “governance” powers. It rather guaranteed an authoritative and regulated presence precisely in the most delicate passages, where prudence, protection and responsibility were needed together.

On 9 February 2007 the Statute was approved by the Pontifical Council for the Laity (copy published above). In that same text, at point 2.2.4, one reads: «The Governing Council adopts its deliberations with the majorities provided for by can. 119 of the Code of Canon Law and with the approval of the Ecclesiastical Counsellor». In light of this datum, it is difficult to understand how today one can maintain that such provisions are improper or incorrect. If they had been considered legitimate and approvable then, on what basis – and with what argument – would they become unacceptable today?

Obedience to the Church

Keeping in mind elements that are not marginal, it must be acknowledged that the observations of the Dicastery, considered in the abstract, have their own coherence: pointing out that certain provisions can open spaces for abuses of authority, for a possible interference between internal forum and external forum, or for a compression of freedom and confidentiality falls within the task of oversight. Carrón, and with him the Memores Domini, have shown no resistance in principle: obedience is not the controversial point, so much so that they immediately set about receiving the requests and preparing the necessary amendments. Moreover, the terrain evoked by the Dicastery is that of risk, not of ascertainment: as Farrell himself has repeated on several occasions, no abuses that occurred are being contested, but rather the possibility that a normative framework would make them practicable. It is clear that those who have not committed abuses and those who have not suffered them naturally tend to perceive that risk as remote, while the Directory – moreover – does not arise from a personal act of Carrón, but from a work elaborated in a lay context. The Ecclesiastical Counsellor approved it, as the same norms provide, with the entire Governing Council. The text was then also submitted to all the Memores at Riva del Garda. No one raised any critical issue. Not even those who in 2018used this pretext to target the President of the Fraternity. In that same year, therefore, having taken note of the Dicastery’s objections, the Memores move to intervene on the provisions, convinced that the matter would be closed on the regulatory plane.

The fact that “all this is not enough”, and that the game will move elsewhere, is what we will reconstruct in the next instalment of this investigation.

fr.E.V. and M.P.

Silere non possum